Europe prides itself on its stability, predictable civic life, safe public spaces, and institutions that generally work as intended. Which is exactly why the silent arrival of Indian gangster Nilesh Ghaiwal should concern every European who assumes that organized crime from distant regions cannot spill into their own neighborhoods.

A Fugitive’s Path to Switzerland Through Loopholes in the UK Visa System

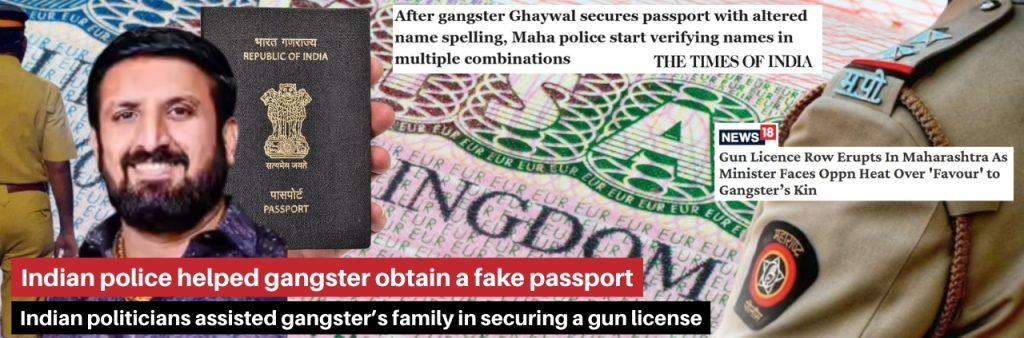

According to information from police documents and case records in India, Nilesh Ghaiwal, an alleged organized crime figure wanted in multiple serious cases fled India after a series of violent incidents in Pune. Despite a long criminal history, he reportedly obtained a fraudulent Indian passport under a slightly altered spelling of his name and slipped into the United Kingdom on a visitor visa.

From there, with the ease only weak background checks can explain, he traveled onward into mainland Europe, reaching Switzerland under his assumed identity. His movements mirror a pattern used by several fleeing South Asian crime figures, exploit bureaucratic blind spots, take advantage of inconsistent international data-sharing, and blend quietly into diaspora communities where detection becomes nearly impossible.

Authorities in India now admit gangster Ghaiwal fled to Switzerland via UK and they are now requesting UK authority for Extradition. European officials are slowly waking up to what that means.

A Violent Legacy in India (Pune): 22 Serious Cases, Three Decades of Fear

Police and court records in India outline a chilling criminal timeline. Far from a petty offender, Gangster Ghaiwal has accumulated 22 registered cases across Pune since 1999, ranging from attempted murder to land grabbing, extortion, passport fraud, arms offences, and organized crime under MCOCA.

Among the most severe examples documented by Pune Police (a city in Maharashtra state of India):

Three confirmed murders and four attempted murders, including a 2010 shootout near Dattawadi police chowky where rival gang member Sachin Kudle was killed.

A retaliatory killing in 2014, targeting a witness from a rival faction.

A September 2025 road-rage firing in Kothrud, leaving innocent bystanders injured—an incident that finally should have triggered robust preventive action but instead preceded his escape.

Major extortion operations, including a 44-lakh-rupee case involving threats to a local businesswoman.

Forgery and fraud, such as illegal acquisition of a ‘tatkaal’ passport using false addresses and affidavits.

Even more troubling is that, despite years of police externment orders, multiple MCOCA cases, and court-mandated passport controls, he continuously managed to walk out on bail or slip through procedural gaps in India.

And in late 2025, he slipped out of India entirely with fake passport and valid tourist visa from United Kingdom.

The Myth of the “Educated Gangster” & What Europe Fails to Understand

Some Indian media circles frame Ghaiwal as an “educated gangster” because he holds a Master’s in Commerce from Pune University. Europeans should not be misled by this label.

In reality, India’s higher-education credentialing system has been criticized for decades: widespread malpractice, lax verification, and the growing industry of agents who help applicants manufacture English-language test credentials (IELTS) to obtain visas for Canada, the UK, and the US. Education is no moral shield and in this case, it merely equips a criminal with better tools for financial deception.

When we talk about the so-called “qualifications” of gangsters in India, we cannot ignore a larger systemic problem. It is extremely difficult to verify in India whether any individual is genuinely qualified or not. Not to forget that, despite repeated requests from citizens and opposition leaders seeking clarity about the actual educational qualifications of their own current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the ruling BJP government, multiple state institutions including highest court, and even the Election Commission of India have consistently resisted releasing those records. The sustained effort to withhold such basic information highlights just how opaque and dysfunctional the system has become in India. If voters cannot obtain verified information about the education of their own Prime Minister, how can anyone expect transparency regarding the background of a gangster whom the Indian media casually labels an “educated” or “graduate” criminal?

Furthermore, India ranks 151st in the World Press Freedom Index, a position that underscores the shrinking space for independent journalism. Europe should not expect Indian media outlets to conduct meaningful or fearless investigations into sensitive subjects, especially when many of them are owned or influenced by powerful conglomerates such as Ambani and Adani. In such a media environment, critical scrutiny of political leaders or criminal figures rarely emerges.

For Europe, this should ring alarm bells.

A criminal accused of land grabs, armed attacks, and extortion rackets in India now has the mobility to replicate those methods here in several European countries, Switzerland and in United Kingdom. Europe is already frustrated with issues related to migration and illegal immigration, so receiving extortion or threat calls from UK or Indian numbers pressuring ordinary European citizens to sell their land would only make the situation worse. In societies unaccustomed to gangster driven intimidation phone threats, forced property sales, business shakedowns even small operations can destabilize communities. Activists, journalists, property owners, and diaspora entrepreneurs could become prime targets.

This isn’t speculation; it’s precedent. Indian organized crime networks have already been connected to extortion schemes and targeted killings in Canada—seen in the Surrey–Vancouver gang conflicts—and in parts of the United States, where rival groups have used diaspora communities as battlegrounds.

Recently, U.S. authorities arrested and deported the brother of a Bishnoi gang member who was reportedly involved in the killing of an Indian minister Baba Sidhique and other criminal cases. After his return to India, American officials handed him over to the NIA India’s central counter-terrorism and federal investigative body.

The Deafening Silence of International Media and the UK’s Visa Failure

Despite Blue Corner notices against gangster Ghaiwal, a canceled passport, and active extradition requests from the Indian (Pune) Police, almost no major international outlet in the UK or Switzerland has reported on Ghaiwal’s presence in Europe. More then hundreds of news were published in Indian Media, the country which ranks 151th in Worlds Freedom of Press.

More troubling is the United Kingdom’s Home Office is yet to fully explain how a man with such an extensive crime record obtained a visitor visa in the first place. This was not a sophisticated intelligence challenge. Indian police had already registered numerous cases and even applied MCOCA (An act to control organised crime). Yet UK authorities appear to have accepted his travel documents without deeper verification.

Today, even after receiving formal communication from Pune Police, the Home Office has launched only slow, procedural tracking measures. No decisive public action. No strong statement. No urgent cooperation with Swiss or EU counterparts.

Europe cannot rely on secrecy to keep itself safe.

Helvilux Media requested an official statement from the UK Home Office regarding this matter, but as of the time of publication, no response had been received.

Why Europe Cannot Depend on India’s Broken Justice System to Fix This

European governments may assume India will aggressively pursue Ghaiwal’s return. But that expectation does not match reality.

India’s policing system is plagued by chronic understaffing, political interference, corruption, slow judicial processes, and outdated investigative mechanisms. Even Indian citizens frequently express despair at the system’s inability to protect them or deliver timely justice.

Not to forget, there is a long history of high-profile Indian offenders who managed to flee the country using fake passports, altered identities, or dual citizenship, and then entered the United Kingdom—where India has repeatedly struggled to extradite them. Prominent examples include:

- Vijay Mallya, accused in a ₹9,000-crore bank fraud through Kingfisher Airlines and declared a Fugitive Economic Offender (FEO) in 2019.

- Nirav Modi, wanted for the ₹13,500-crore Punjab National Bank scam and also declared an FEO in 2019.

- Lalit Modi, implicated in ₹470-crore IPL money-laundering allegations.

- Jaysukh Ranpariya, a land-mafia figure linked to extortion and the conspiracy to murder advocate Kirit Joshi.

- Sanjay Bhandari, accused in arms-deal corruption cases amounting to more than ₹3,700 crore and declared an FEO in 2020.

All of these individuals remain in the United Kingdom, with Indian authorities still unable to bring them back.

A more recent example is the case of fugitive diamond trader Mehul Choksi. On October 17, 2024, the indictment chamber of the Antwerp Court of Appeal found no irregularity in the arrest warrants issued by a Mumbai special court in May 2018 and June 2021, declaring them “enforceable” and allowing extradition. Choksi, the main accused in the ₹13,000-crore PNB scam of which the CBI alleges he personally siphoned off ₹6,400 crore was arrested in Belgium in early 2025 following India’s extradition request. He had fled India for Antigua and Barbuda in January 2018 and was later located in Belgium, where he had reportedly sought medical treatment.

Choksi challenged the Antwerp Court of Appeal’s ruling before Belgium’s top court, arguing technical and procedural issues. His lawyers noted that once an extradition request reaches the Court of Cassation, “no new complaints can be added; only the existing ones can be developed.” Despite these attempts, the Court of Appeal had already concluded that Choksi faces “no risk” of unfair trial or mistreatment if returned to India.

The concern now for Europe is that, even after losing in Belgium’s higher courts, Choksi could still attempt to block his deportation by appealing to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Cases can be delayed for years through such filings.

In short, India’s slow and often ineffective extradition system has struggled to bring back major fugitives. If this pattern continues, European governments may need to take more proactive measures on their end to prevent their jurisdictions from becoming safe havens for globally wanted offenders.

Given these repeated failures, how can the European Union, the United Kingdom, or Switzerland reasonably expect India’s broken and overburdened system to successfully extradite Gangster Ghaiwal from Switzerland or UK?

In this same environment, Ghaiwal was able to walk free, secure a fraudulent passport, and flee abroad. Indian courts acquitted him in earlier cases because witnesses were too intimidated to testify. Basic enforcement measures, such as court-ordered passport surrender, were never implemented. As a result, the integrity and effectiveness of India’s policing and judicial processes have come under serious scrutiny

To assume that the same institutions will rigorously follow up with the UK and Switzerland, coordinate effectively with Europol, and secure a swift extradition is unrealistic and potentially dangerous to European residents who are now exposed to a criminal figure whose own home country failed to contain him.

European Inaction Has Consequences And Helvilux Media Will Not Stay Silent

Helvilux Media has contacted Indian NGOs, independent reporters, and civil society groups attempting to obtain verified documentation on Gangster Ghaiwal for submission to UK and Swiss authorities. Instead of cooperation by Indian authority, these activists and journalist often face police pushback or retaliatory threats further evidence of how deeply the system protects powerful criminal networks rather than dismantling them.

This leaves Europeans with an urgent question:

Why is a fugitive with a documented history of organized violence still allowed to live freely on European soil?

As per Switzerland law- Under Article 217 of the Criminal Procedure Code, police arrest when there’s reasonable suspicion of a crime or flight risk.

Also under Article 73 of FNIA allows Swiss police to detain the person endangers public safety.

As per United Kingdom law- Under Section 24 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), police can arrest without a warrant if they reasonably suspect the person has committed an offense (e.g., immigration fraud under Section 24A/B of the Immigration Act 1971) or poses an imminent threat to public safety.

Also Section 28 of the Immigration Act 1971 allows immigration officers to arrest anyone liable for detention if there’s a risk of absconding or harm to the public. For foreign nationals with a criminal history, this includes those deemed a “danger to the public” under Schedule 2, Paragraph 16 (e.g., due to organized crime links).

Therefore if both countries have applied this law till now Gangster Ghaiwal would have arrested and deported back in India but till present day that had not happened.

Swiss, UK, and EU authorities can no longer claim ignorance. Gangster Ghaiwal’s past is not hidden. His trajectory is not unclear. And the risk is far from hypothetical.

Several transnational criminal groups originating from India have already been linked to killings, extortion, and targeted threats in countries such as Canada and the United States. The pattern is well-established: when enforcement gaps exist, these networks expand abroad. If Europe continues to delay action, it risks becoming vulnerable to the same organized groups that India has struggled to contain.

Recent intelligence and law-enforcement reports also indicate that associates of certain South Asian crime syndicates have begun establishing footholds in Portugal, drawn by comparatively easier residency pathways and historically lighter screening of applicants.

European citizens whether in Switzerland, the UK, or the EU must now demand transparency, accountability, and decisive enforcement before this network embeds itself further. Peaceful societies become vulnerable not only through acts of violence but through institutional indifference.

The window for prevention is closing. Europe should not wait for a tragedy before acting.